Even though I already know it’s foolish to say this online, I’m still furious with Jordan Peterson. I’m angry because he forced me to read a 505-page book about God that was nearly unreadable, and I’m angry because I now have a splitting headache and, worse, a head full of verbose sophistry and foolish misogyny from a big-word spouter dressed like a would-be St. Augustine, dressed in the robes for Russell Brand.

“As you get a deeper understanding of the nature of your society and your soul, set yourself straight in intent, aim, and purpose. Join Jordan Peterson as he explores the most amazing tales ever told. Have the courage to challenge God.

Accordingly, Peterson’s new, heavy doorstopper, We Who Wrestle with God, comes with a self-aggrandizing press release that is as ambitious as it is impossible for the average reader to understand. A lesson on making too many promises and not living up to them, if there ever was one.

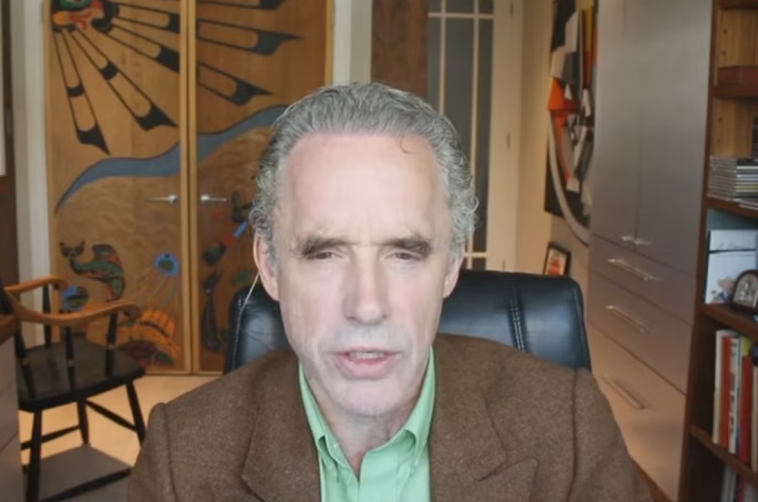

I’ll give this for the highly controversial pop-psych “public intellectual” who decided to make outrageous sums of money telling young men to “straighten up and fly right” on YouTube instead of lecturing: he doesn’t hesitate to set lofty goals. There is hardly a more challenging subject to address than the Creator Himself. This wasn’t always the case for Peterson, who was raised in a rather Christian household in Alberta, Canada, the son of a schoolteacher father and a librarian mother. After embracing revolutionary socialism and rejecting Christianity completely in his teens, Peterson went back to what he calls a “traditional” understanding of the universe and the Good Book. After earning degrees in clinical psychology and political science, he started teaching at Harvard and then moved to Toronto to become a professor. There, he married and had a daughter named Mikhaila, who also does podcasting.

In order to make the case that the archetypes found in the Old Testament serve as the prism through which we are preprogrammed to view the world, the book follows us through some of its most important passages. The Tower of Babel is a timeless lesson in hubris; Abraham is the first true adventurer; Moses is a hero and savior of the oppressed; Jonah is the ultimate warning against shirking responsibility; Cain and Abel is a cautionary tale about not giving your all (and, of course, the perils of sibling rivalry); Noah is the only Good Man in a sea of chaos; and Adam and Eve are the eternal father and mother of all and the causes of sin. Peterson tries to draw basic conclusions about God’s character from these stories.

If it seems strange to argue that the foundation of Western society as we know it is based on Christian principles while focusing on the Old Testament rather than Jesus, do not be alarmed! Peterson is preparing a completely other book about the New Testament that is probably just as hench. However, despite my best efforts to wriggle my way through the maze of waffle and bluster, excessively archaic language, and broad, unambiguous claims that pass for absolute facts, I keep returning to the same questions: for whom is this book intended? What is the purpose of it? And why in hell was it written by a disgraced former psychology professor?

A brief review of Peterson’s development during the previous ten years offers some hints on this final aspect. Despite being mostly unknown outside of academia, he continued to teach clinical psychology at the University of Toronto until the mid-2010s. Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief, his debut book, was released in 1999. In 2013, he launched a YouTube channel and posted some of his scholarly lectures. So far, so blah.

Peterson then started creating social media videos in 2016 criticizing Canada’s Bill C-16, a law that forbade discrimination against gender identity and expression. He gained almost two million YouTube subscribers in just two years as a result of his anti-trans attempts to enter the culture wars. Around this period, he became dependent to the benzodiazepine family depressant Clonazepam, an anti-anxiety medication. By 2020, his addiction had gotten so bad that he had to fly to Moscow to be put in a medically induced coma (after being refused this treatment in North America). He spent eight days in that condition, then spent a month in critical care, but later that year he declared himself well again.

Even as his addiction set in, Peterson’s fame grew in 2018 after his second book appeared on international bestseller lists. A compilation of self-help writings called Twelve Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos, which catered primarily to disillusioned young males, was a huge commercial success. It combined pseudointellectualism with commonsense advice. He was featured in The New York Times and asked to share his opinions on podcasts like the Joe Rogan Experience, where he disclosed that he only eats beef, salt, and water, probably in an attempt to Make Scurvy Cool Again. He also sold out 1,000-seat venues during a global book tour.

In the meantime, Peterson became the unofficial patron saint of the manosphere after he declared that “enforced monogamy” was a reasonable solution to lonely men committing mass murder and that the current hierarchy, which sees men dominate positions of power, “may be predicated on competence.” These statements sparked accusations of misogyny. In an instant, “Jordan Peterson” went from being a sensation on the internet to becoming well-known.

In the midst of all of this, his own profession betrayed him. In 2020, Peterson’s claimed “transphobic, sexist [and] racist” remarks were examined by the College of Psychologists of Ontario’s Inquiries, Complaints and Reports Committee. He was ordered to undergo particular training in 2022 after it was determined that his public utterances contained language that was “disgraceful, dishonorable, and/or unprofessional” and that “posed a moderate risk of harm to the public” by “undermining public trust in the profession of psychology.” He denied any misconduct and disputed the allegations.

Given the similarities—a whirlwind that took him from relative obscurity to a beloved influencer with millions of contemporary disciples and, later, to a “martyr” punished for his beliefs—it may not be surprising that Peterson would feel empowered to address the subject of the Messiah. His thoughts on God and biblical metaphor are clearly not new, but this most recent attempt is the first time he has devoted an entire book to the topic.

One must admit that reading We Who Wrestle with God is a very odd experience for a practicing Christian. Peterson’s decision to use his tremendous influence to support an endeavor as valuable as promoting biblical knowledge to a modern audience is something I, of all people, should be thankful for. The Bible and its teachings, after all, are the foundation of Western civilization in a way that has been all but lost in a culture that is becoming more and more secular. I don’t dispute that. Theoretically, I am all for the Good Book’s teachings to reappear in popular culture. It took me only a few pages to realize that Peterson’s most recent effort is not going to be helpful to the cause.

This author doesn’t seem to want his reader to comprehend; there is no effort made to make concepts clear, intelligible, or even concise.

I have to start by asking again: for whom is this book intended? I’m at a loss as to how to solve it. It’s hardly targeted at academics, a specialized literary market that doesn’t usually justify intensive and costly advertising and promotion. If it were, there could be legitimate concerns about Peterson’s suitability as a psychology professor rather than a theologian. (In a moment of obviously unintentional irony, Peterson writes: “Genesis 2 therefore extends the characterization of God, presenting him as the spirit that warns against overreach – against the cardinal sin of pride. What might overreach mean?” Hmm, maybe the idea that you can just jump in and publish the next Very Important Book about the Divine because you’re interested in it, not an expert on it.)

Therefore, it must be assumed that this book is intended for lay readers, making basic truths about the human condition as they are presented in the Bible’s stories accessible to the general public. However, its interpretation also fails to withstand scrutiny.

The experience of struggling through We Who Wrestle with God is fundamentally unpleasant. It would seem strange to write a bewilderingly dense book if you truly wished to introduce a new generation to the advantages of putting God and biblical morality at the center of a decent society. One feels obligated to keep pausing to take in sentences once, twice, or three times while navigating the maze-like mist of academic jargon and self-important bombast, yet the meaning is still elusive.

I feel like I’m slowly going insane when I read phrases that seem to be expressing universal truths but, upon deeper examination, actually mean… what? What about the following: “The Great Father is the a priori structure of value, derived from the actions of the spirit that gave rise to such structure, and composed of the consequences of its creative and regenerative action”?

The book is over 500 pages long, which is not surprising given that 100 words are used practically everywhere when ten would be more appropriate. It’s possible that Peterson is the literary personification of the new intellectual movement. This author does not seem to care about his reader’s comprehension; there is little effort made to make concepts clear, concise, or even comprehensible. Instead, it’s the style of someone who wants to show that they are extremely intelligent by burying meaning beneath an obscure “word salad” that would probably fall apart if you ever knew what was being said. Sadly, that is as pointless an endeavor as attempting to affix mist to the wall.

Peterson purposefully and tellingly employs the King James version of the Bible rather than the considerably more popular New International Version when quotes from it in We Who Wrestle with God. The former translation was completed in the early 1600s, and although many literary types enjoy its poetry and lyricism, it is all “spaketh” this and “goeth” that—old terms that were rendered obsolete centuries ago—and merely acts as an instant and needless obstacle to understanding for the present reader. It should come as no surprise that Peterson frequently uses words that were last in use 200 years ago (think “import” instead of “importance,” “privation” instead of “deprivation”—it’s like stepping into Pride and Prejudice).

The book thus reflects the strategy that has propelled Peterson to his current status as a “public intellectual”: a projection of brilliance based on the flimsiest foundation, a potent concoction of outdated terminology, whataboutism, posturing, and obfuscation. He must be intelligent because I don’t fully comprehend what he’s saying!The audience assumes, rather than questioning why a man with such intelligence is incapable of articulating himself clearly. Therefore, when he occasionally makes a comment that is understandable, it’s difficult not to cling to it like a life raft in the midst of the uncertainty. This is problematic because what he’s saying is as likely to be really sexist rhetoric as it is to be sound life advice.

According to atheistic academic Richard Dawkins, debating someone like that is like battling a shape-shifting sand opponent since there is nothing substantial to grasp. For instance, Peterson delivered a master class in straw man arguments masquerading as replies when Dawkins directly asked him if he believed in a literal Virgin birth. Peterson finally conceded, “These questions… They don’t strike me as… They’re not getting to the point.”

Truthfully, beneath the book’s sloppy grammar and technical jargon, like in many of Peterson’s works and talks, there lie some sound, timeless principles and pearls of wisdom. Sentences such as “there is no sense in establishing a society that fails to care for the people who compose it at every stage of their development, from vulnerable to able, productive and generous”—a profoundly socialist-sounding worldview that Peterson draws from Deuteronomy—will be gratefully nodded along with.

Similar to all of Peterson’s works and talks, underlying all the nonsense lurk harmful ideologies.

However, beneath all the junk, as in many of Peterson’s publications and talks, there are also dangerous views. There are serious concerns with his approach to “interpreting” the Bible. Rather than examining the stories and archetypes to learn more about human nature, he reverse-engineers hypotheses by observing the world, determining what he believes men and women to be like, and then applying this confirmation bias to the Bible in the past. One example is Peterson’s interpretation of Adam and Eve and the Fall, in which he comes to the conclusion that Eve’s choice to give in to temptation and consume the forbidden fruit was driven by the sin to which “all” women are vulnerable: a conceited and “all-encompassing” mercy. But the myth doesn’t explain Eve’s motivation, so we don’t know. It is more like starting with 5 and conclusively asserting that the sum must have been 2 + 3 rather than adding 2 + 2 and getting 5; it may have been 1 + 4, 2.5 x 2, or even 20 ÷ 4.

Speaking of Eve, Peterson also utilizes her as a springboard to present a worldview that views women as having little intrinsic value outside of their roles as mothers. Perhaps the fact that the sacred picture of women is more of a woman and newborn than a woman is no accident. By herself, what is a woman? He writes, “a target of transient sexual gratification.” The classic Madonna/whore paradigm, ah! A cliche as ubiquitous as it is harmful.

I can only assume that Peterson isn’t quite as smart as he believes he is, though I’m sure his many admirers will say otherwise. The ability to utilize intelligence to make difficult ideas understandable is, in my opinion, the real test of a public intellectual. Finding a way to effectively convey concepts so that your audience can follow along, comprehend, and possibly be persuaded by what you’re saying is more important than simplifying things. For instance, CS Lewis was a master at theology; through his theological essays and allegorical fiction, he was able to communicate the most profound truths and loftiest ideas about the nature of God. Though they could have more discriminatory arguments to make against childless women, I doubt anyone would learn anything more about God by the end of We Who Wrestle with God.

The silver lining in all of this? I seriously doubt that many people will read Peterson’s book. Without a doubt, they will purchase it, put it on bookshelves and coffee tables, and occasionally quote it incorrectly in public. However, push through those dreary 505 pages? It’s unlikely. Ultimately, battling God himself would undoubtedly be less exhausting than battling Peterson’s cumbersome, incomprehensible “magnum opus.”